Table of Contents

In this blog post, our writer, Charlotte Bateman, shares a personal account recounting her unique experiences with Braille.

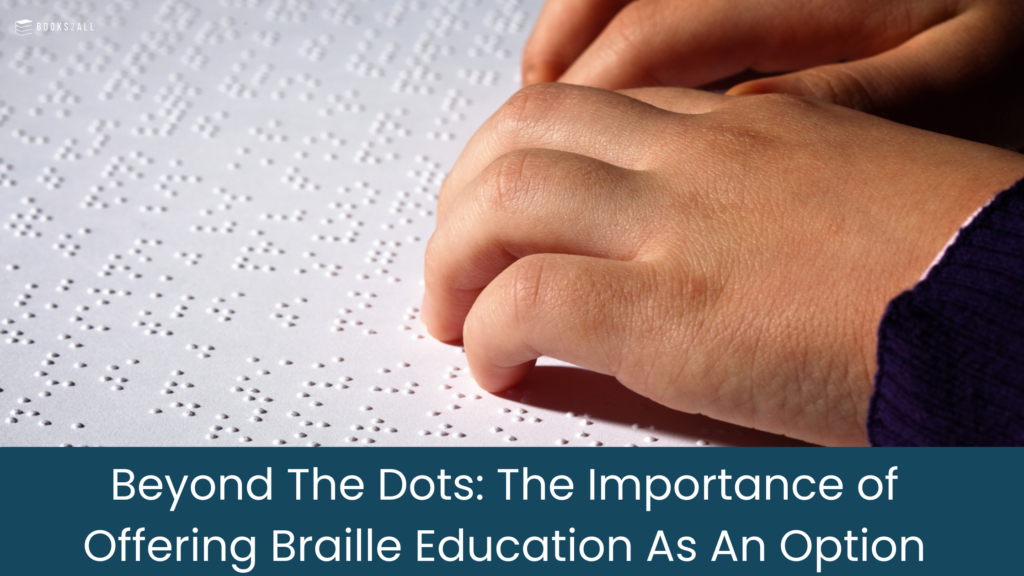

When it comes to famous inventions, there are certain ones that just roll off the tongue. For example, the light bulb was invented by Thomas Edison, and the telephone by Alexander Graham Bell. These inventions from the 1800s have changed the way we live and communicate forever. But there’s another brainchild born in the 19th century that is rarely ever talked about, despite being just as revolutionary. And that’s Braille: the system of raised dots that has allowed blind people to read by touch for 200 years.

Charles Barbier’s Vision: Night Writing for Soldiers

Its history began in the early 1800s with a Frenchman and military veteran named Charles Barbier. During his time in combat, Charles noticed a major barrier faced by himself and his fellow soldiers. They had to use lamps when reading military messages at night. Because of this, soldiers were often caught, and subsequently killed. It gave Charles the idea to develop a unique system that would allow the soldiers to read in the dark. Known as ‘night writing’, the code was based on a raised 12-dot cell in which each dot and combination of dots represented a different letter or phonetic sound.

The method was not just intended for soldiers. Charles realised it could also make reading accessible to people with sight impairments. The only problem was, that having 12 dots in the cell meant each letter could not fit under a single fingertip. But in 1820, an 11-year-old boy from Paris set out to solve this defect. His name was Louis Braille.

Louis Braille: A Visionary at Eleven

From the age of three, Louis had lived with no sight following a terrible accident in his father’s leather workshop. He had been playing with tools and as he went to punch a hole in a piece of leather, the tool slipped. It stabbed itself in his right eye, leading him to become totally blind. However, this disability didn’t stop him from excelling in education, particularly music, or from landing himself a scholarship at age 11 at the National Institute For The Blind in 1820. It was while enrolled at the school that Louis was introduced to Charles Barbier’s ‘night writing system’. Fascinated, Louis began making raised dots with one of his father’s instruments at home. He experimented with different patterns of dots that would make the method more accessible for his visually impaired classmates. By 15, he had cracked it and modified the 12-dot cell to just 6 dots, which could be felt with one fingertip.

The code proved a huge success and it wasn’t long before people with sight loss in other countries were being taught to read Braille. Then, around seven decades later, an American teacher for the blind decided to refine it even further. His name was Frank Hall and he designed the first Braille typewriter in 1892. It was eventually replaced by the Perkins Brailler in 1951 which was invented by David Abraham, an English immigrant with a background in manufacturing.

A Personal Journey: Braille in the 21st Century

Today, people are still being taught to read and write in Braille. However, the skill is rapidly depleting. In 2022, figures from The RNIB showed just seven percent of blind and partially sighted people in the UK read Braille. The question is, has Braille become outdated? Do we really need it when there are so many technological advances? Or, on the contrary, does this tactile way of reading still hold value and relevance?

As a 22-year-old blind journalist who uses Braille almost every day, I would strongly argue for the latter. I was taught Braille at a mainstream school, not long after losing my sight aged four. While my peers began stumbling over the words of Biff and Chip, I was doing the same- except instead of reading with my eyes, I was following lines of dots with my fingertips. When it came to writing our own little stories in class, I was also able to participate. I would tap away on a Perkins typewriter and every time I reached the end of a line, it would ding with a tiny bell. Then, my teaching assistant who could read Braille by sight, would carefully scribe my work so that the teacher could mark it.

I’ll be honest, I was relieved when I was given an electronic Braille machine in Year 4, as I’m sure my support staff were. The Perkins was like a massive brick that would have almost certainly shattered your bones if you dropped it on your foot. And aside from the fact it made my fingers ache from pressing down the stiff keys, I reckon the noise must have been pretty annoying for my classmates. Paper Braille could be another nuisance as the dots took up more space than print, making the books ridiculously thick. I will always remember ordering the first Harry Potter book in Braille and my mum staggering out of the post office with a tower of cardboard boxes. If I recall correctly, it was in 13 volumes.

The BrailleNote was the first version of a Braille computer. It had the normal six keys, as well as a backspace and enter button, and instead of a screen, what you were typing would pop up in Braille below the keyboard. Perhaps the coolest thing about it was that it had all the functions of a basic computer. You could surf the internet, send emails, or play games. You could even hook it up to a printer.

At secondary school, I was taught to use a Windows laptop. It had a screenreader on it called Jaws which sounded a bit like a robot, and I hated it. The school would have to push me to use it in lessons when all I really wanted to type on was my Braille computer. Then, around the age of 13, I got an iPhone for my Birthday and it was a game changer.

Like Windows, Apple has its very own screen reader called Voiceover. It’s featured on all their devices, and in my experience I’ve found it to be a lot faster and easier to use than Jaws (oh, and a lot more bearable to listen to). If I could only take three items with me to a desert island, my iPhone, with an endless supply of mobile data, would probably be one of them. I can do pretty much anything on it. I can text; research; play music; and watch TV. And there are all sorts of incredible apps now too, like See Ai where you can photograph say a printed-out document, and it will read it out to you.

During my last years at school, I got an Apple Mac. I would sometimes use it for writing essays or making presentations. I still used my BrailleNote more though. There were certain things that I struggled with when relying on audio alone. For example in lessons, I found it difficult to make notes on a laptop, because I would be trying to listen to the teacher whilst simultaneously listening to my Voiceover babbling away in my headphones. With the BrailleNote however, there was no audible distraction and I could read back my notes in peace. It also meant I could participate in English lessons when we would go around the class reading aloud Shakespeare or whatever set text it was that term. I would have the document open on my BrailleNote, and I could just follow along. One other great thing about having a Braille computer was that nobody could see what you were writing, so technically you could browse TV spoiler articles or go on Twitter and the teacher would be none the wiser. Not that I ever did that. Well, hardly ever.

At both GCSE and A-Level, I decided to write all my exams on the BrailleNote. And to this day in my job as a journalist, I would say it’s still an invaluable gadget. I will often type full articles on it like I did for this very blog post. But even if I type an article on my laptop, I still rely on Braille when editing it. For example, if you listen to an article, you will hear typos and mistakes you’ve made. However, what you may not pick up on from the audio are more subtle things like if you’ve missed a comma or put a capital letter in the middle of a sentence. Because of this, I will always email the document from my laptop to my BrailleNote, so that I have the article physically in front of me to read.

Of course, I’m one person in about two million visually impaired people across the UK. And there will be lots of people out there who prefer just using audio, and that’s great. For me, I think the key is to open blind children up to all options so they can work out what works best for them. And I think it’s really important that we don’t dismiss Braille as this outdated system because it isn’t. Yes, we might be past Perkins bricks and 13-volume novels. But like the light bulb and the telephone, Braille has adapted and evolved into even more powerful technologies that fit in with our current lifestyles.

The last thing I would add is, that research has shown that learning Braille as early as possible is crucial. This is because you can lose finger sensitivity in adulthood. So with that in mind, local authorities and schools have a responsibility to ensure all children who are blind do not miss the boat on learning a skill that could potentially change their lives.

Fantastic article by Charlotte