We are all familiar with the idea of ‘losing yourself’ in a story. However, for a child with vision impairment, this process of becoming so deeply engrossed in what you are reading that the real world ceases to exist may coincide with ‘finding yourself’. I’ll return to this idea later.

The power of books to transport a child beyond their immediate world can certainly be a big factor in fostering a lifelong love of reading. My earliest memory of this kind of immersive reading experience is that it happened, I think, on my first visit to the Faraway Tree and became particularly potent a few years later when I travelled extensively through Narnia.

I work for the Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB) in the children, young people, families and education team. We provide a range of services for families of children with vision impairment and the professionals who support them. Across the UK, it’s estimated that over 25,000 children aged 0-16 have a vision impairment: that’s around two children out of every 1000 who may require a high level of specialist provision to learn on equal terms with sighted children.

Accessibility is key to encouraging these children to read

Whatever adaptations a child needs – and these can range from straightforward enlargement to books produced in Braille – library services provided by charities like RNIB and Guide Dogs can supply them. Other organisations such as Living Paintings and Clearvision Project do the most wonderful work, too, incorporating tactile and auditory experiences to bring stories alive for children with vision impairment.

Depending on the extent of their vision impairment and accessibility needs, teaching a child to read can require the skills of a specialist. Qualified teachers of vision impairment (QTVIs) hold additional qualifications to enable them to assess, plan for and deliver quality teaching interventions for children with vision impairment.

Right from the early years and throughout their education, the QTVI will play a key role in supporting a child through learning to read according to their individual needs, using different materials to help them develop the skills most relevant and useful to them.

At home, parents can encourage reading in children with vision impairment from an early age in much the same way they would with a sighted child. By sharing simple, repetitive songs and rhymes with babies and talking about the world around them, parents help children discover the wonder of everyday life and encourage a desire to create stories from their own imaginations, thus developing early literacy.

I asked some of our families for their ideas of what worked best when approaching reading with a child with vision impairment, and top of the list was taking a multi-sensory approach:

“Use objects related to the characters, dress up in costumes or fancy dress, or even funny hats. We’ve even used a spritz of perfume for characters or different pieces of fabric to indicate their clothes. Use pots and pans to make onomatopoeic words (‘Bang!’ ‘Crash!’ ‘Whoosh!’). Use all your silliest voices for each character…let those dramatic juices flow.”

Sensory experiences make stories meaningful

An important thing to remember about children with vision impairment is that their conceptual understanding of the world takes time to develop and often requires explicit teaching. Pause for a moment and think about when you first learned about the sky. The chances are, if you always had good vision, there was no moment of enlightenment.

The sky was always there above you as you were pushed along in your pram; the ribbon of blue across the page in most of your earliest picture books; a constant, if intangible, presence that nobody ever really had to explain. Not so for children with limited or no vision, according to Paths to Literacy: “For children with vision impairment to further understand their world, they must build concepts through purposeful exploration.”

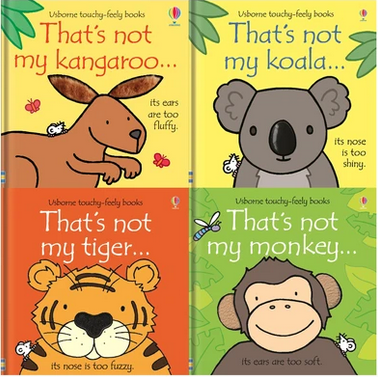

RNIB recommended sensory book examples

Including a range of sensory experiences, such as those described above, is so important when engaging in reading activities. Story sacks – which can be purchased from specialists such as Positive Eye or put together from objects in the home – are a wonderful way to make storytime more interactive and meaningful for children with vision impairment. For some children, it’s all about listening. Audiobooks might appeal to sighted readers because they fit seamlessly into busy modern life but, for those with vision impairment, they can be a game-changer:

“My three-year-old has no vision at all, so it’s been really hard to engage him in sitting with a book; he’s more interested in auditory activities than touch/feel type. However, he absolutely LOVES audiobooks, probably because they have lots of sound effects and music alongside the story, which brings it to life a lot more than I can by reading to him!”

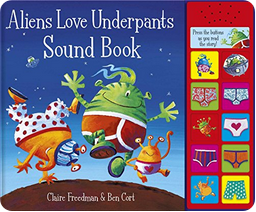

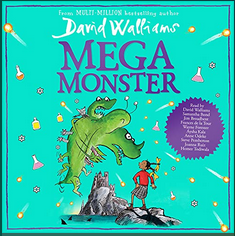

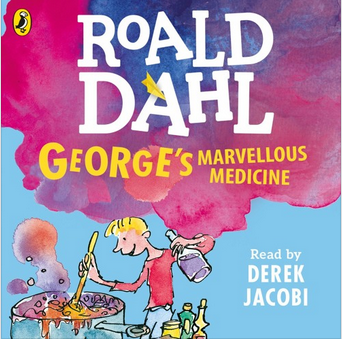

RNIB recommended audiobook examples

Finding yourself from positive representation in books

Returning now to my opening comments about ‘finding’ yourself in books – this can apply to all of us in the sense that the process of reading may help us gain a better understanding of ourselves, our place or purpose in the world. However, I am talking about something less philosophical but, arguably, more significant in this context. For many children with a disability, seeing themselves represented positively – in a book, a toy, a film character – can have the most profound impact on their self-esteem. Again, our parents are happy to explain:

“It’s important for kids and young people to see themselves modelled well. Thankfully authors have gotten a lot better at this over the years, and the patronising tone of some older books is disappearing. That sense of ‘This is Jonny, he has a dis-a-bil-ity. Jonny’s friends make sure he is included in their game.’ Rather than as it should be: ‘Here’s Jonny and his friends; they are playing football at the park’.”

It’s encouraging to see positive representation become more commonly accepted as an intrinsic and important consideration when authors (plus toy producers and filmmakers) pitch new ideas. Still, there are bad examples out there, and it may be necessary for parents to do some subtle editing if the language of a text is jarring or could give a child the wrong impression.

One mum, so disillusioned with the lack of representation of children with vision impairment that she wrote and published her own book, Matilda’s Eye Patch, said: “Children need to see characters that reflect them, whether that’s in glasses, wearing a patching or with other VI [vision impairment].”

RNIB recommended positive representation book examples

There is undoubtedly still work to do, but I am optimistic that opportunities for children with vision impairment to lose – and find – themselves in a good book are on the increase.

Thank you for visiting our blog. Our vision here at Books2All is a world where every child finds the books that help them reach their true potential. If you have spare books in good condition at home that you think might be appropriate for school children, please sign up for our app’s pre-release waiting list. If you represent a school, please register to receive books for your students.

Hello would love to hear more about the books and work you do.

Hi Jennifer,

We would be delighted to. Please can you tell us what in particular you would like to know about?